By Arshi Husain ’26 and Monty Krakovitz ’25

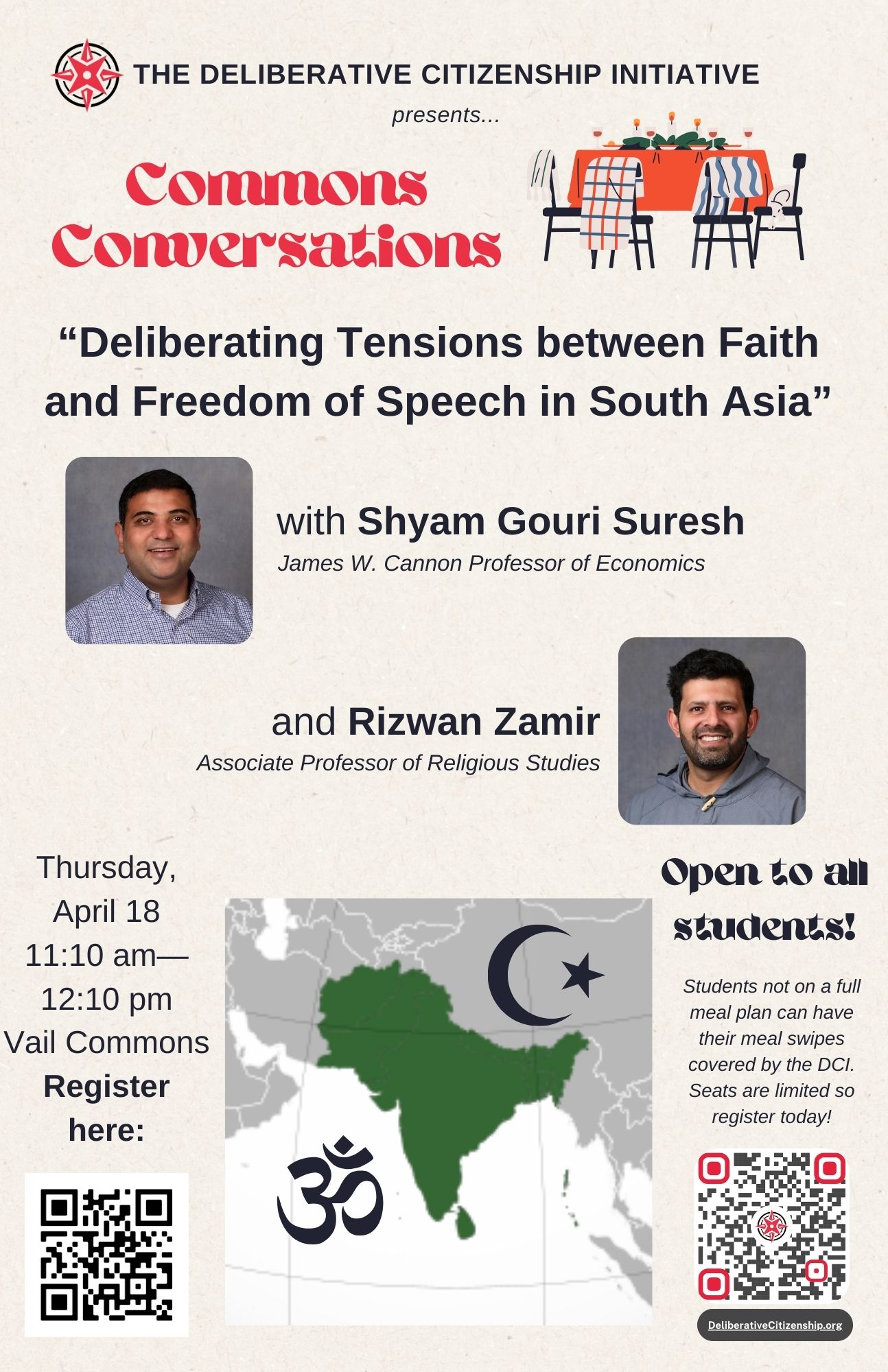

On April 18, 2024 in the Commons Annex Room, the Deliberative Citizenship Initiative hosted a Commons Conversation on “Deliberating Tensions between Faith and Freedom of Speech in South Asia.” The conversation was facilitated by DCI Fellows Arshi Husain ’26 and Monty Krakovitz ’25, the authors of this post. We were joined by Professor of Economics Dr. Shyam Gouri Suresh and Associate Professor of Religious Studies Dr. Rizwan Zamir, who helped jumpstart the conversation by sharing their perspectives on the topic at hand. The students then contributed their thoughts and questions, and a lively and engaging discussion followed.

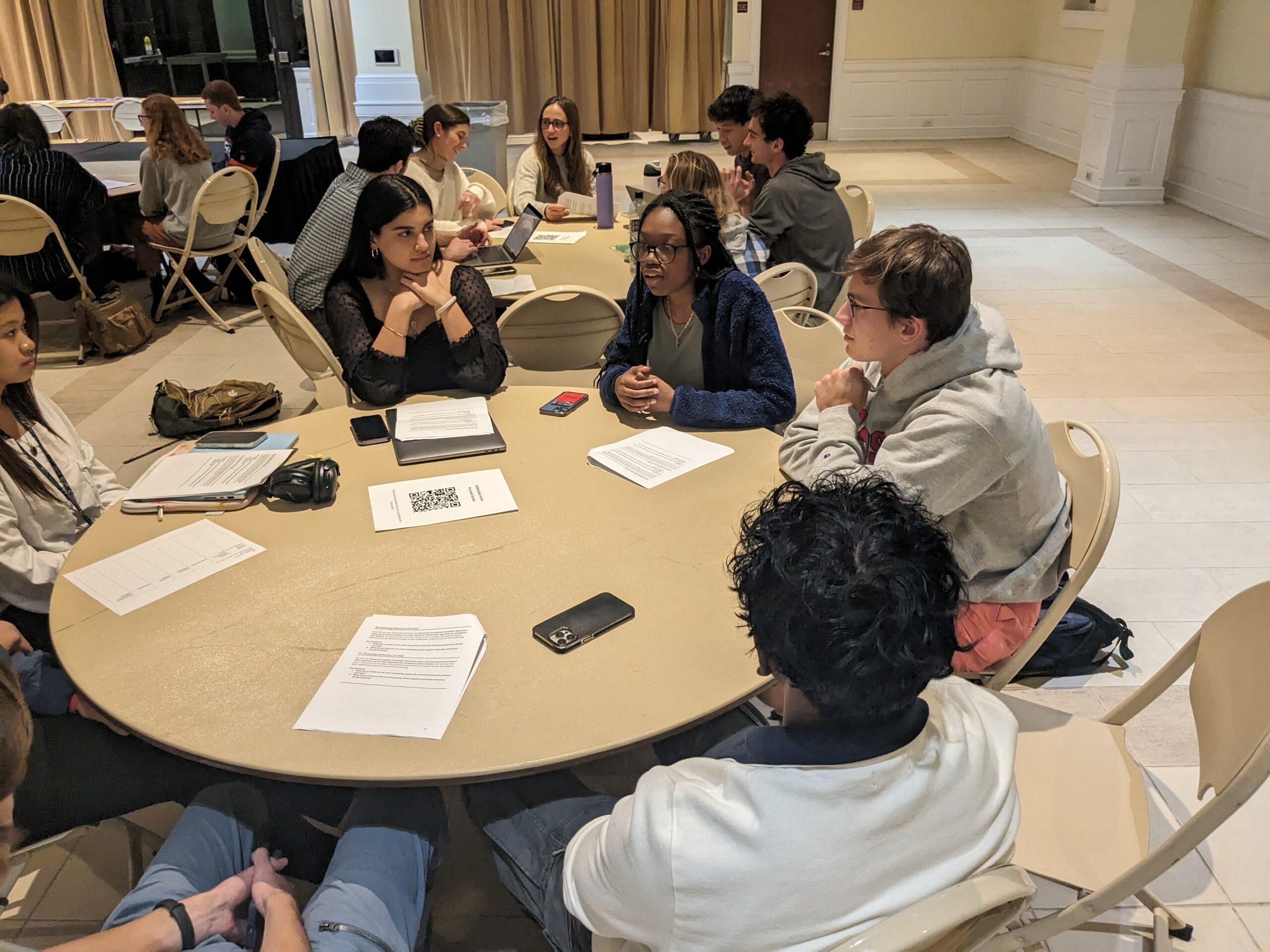

Our conversation centered on the tension that sometimes arises between faith and free speech, specifically in the South Asian area. However, not only South Asian students from India and Pakistan joined the conversation but also students from around the US and various countries such as Greece and Egypt. In total, a group of 12 students from a range of different backgrounds participated in the deliberation.

One of the professors leaned more towards the position that offending the religious sentiments of citizens in the India/Pakistan area should not be punished by the government because citizens should be able to critique ideas without interference. The other professor leaned towards the position that free expression can be a virtue in some circumstances, but there are other virtues that are more important and are often forgotten on the never-ending quest for inclusivity. In other words, arguments tend to become complicated when we are weighing one virtue (freedom of speech) against another virtue (inclusivity).

Interestingly, the conversation spread away from the South Asian area and took on a more global perspective. We further discussed the benefits and drawbacks of putting secularism and inclusivity above truth and virtue. Dr. Zamir stressed that the art of discourse lies in understanding how a particular culture works, and how we can construct our arguments to best fit the mold of a broader society. In other words, in order to see eye-to-eye with others, we often need to be able to view the world from their eye-level.

Dr. Gouri Suresh also shed light on the Indian Penal Code (IPC), which includes several sections that limit free speech. Section 295A prohibits speech intended to outrage religious feelings (enacted by the British in 1927), Section 124 prohibits speech “that excites, or attempts to excite…hatred, contempt, or disaffection” towards the Indian government (enacted by the British in 1870), and Section 153A prohibits speech intended to cause disharmony between groups (enacted in 1860 by the British).[1] This poses the question: how do we navigate questions about free speech in countries that have hindered it for centuries? India, for example, was among the first countries to ban Salman Rushdie’s “Satanic Verses” in 1988—a novel that one Indian elected official claimed was a “deliberate insult to Islam.”[2]

To recapitulate, while our conversation began with a focus on the South Asian region, we were quickly able to draw global connections, understanding that this is an issue that needs to be considered carefully worldwide. We also gained a greater recognition of the historical and legal contexts that continue to play a big role in shaping the discussion around religious liberty, freedom of expression, and inclusivity.

[1] Hate speech laws in India. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hate_speech_laws_in_India; India Code: Section 124A Details https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=133#:~:text=%2D%2DComments%20expressing%20disapprobation%20of,an%20offence%20under%20this%20section; Ananya Bhatia, Weaponization of Colonial-Era Sedition Law: The Future of India’s Free Speech, Columbia Undergraduate Law Review, https://www.culawreview.org/current-events-2/the-future-of-indias-free-speech.

[2] Rewind & Replay | The Satanic Verses: Why it was never just about the book. 2022. Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/rewind-replay-the-satanic-verses-why-it-was-never-just-about-the-book-8091982/.